Feather Thieves Prompt Legal Protections for Vulnerable Birds

In the late 1800’s, birds and feathers became all the rage from fashion to home décor to flyfishing. Hats, jewelry, fishing flys, table displays – the more feathers – and even whole birds – the better!

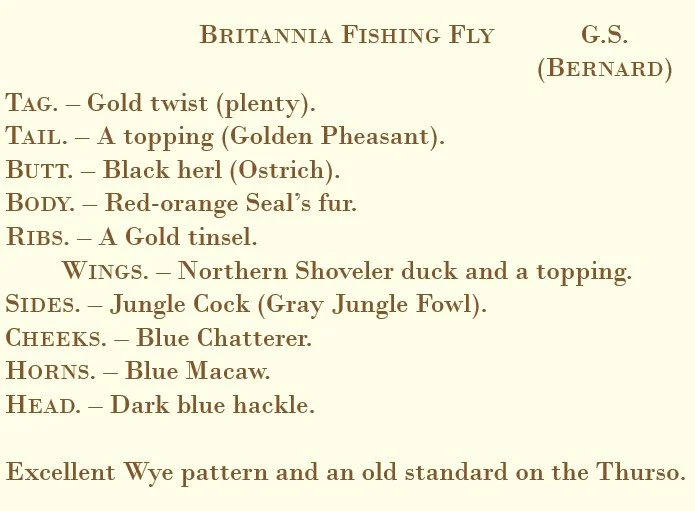

Feather Fanciers. The Victorian Era was a time of rapid social and industrial change. Many well-to-do Victorians found comfort in nature, surrounding themselves with the natural world in their fashion, art, décor, and even sport. Salmon fly fishing, increasingly restricted to private landowners and clubs, was no exception. Each club had its own specialized fly pattern. While salmon do not have a preference, the flies became increasingly elaborate status symbols, using expensive, exotic bird feathers.

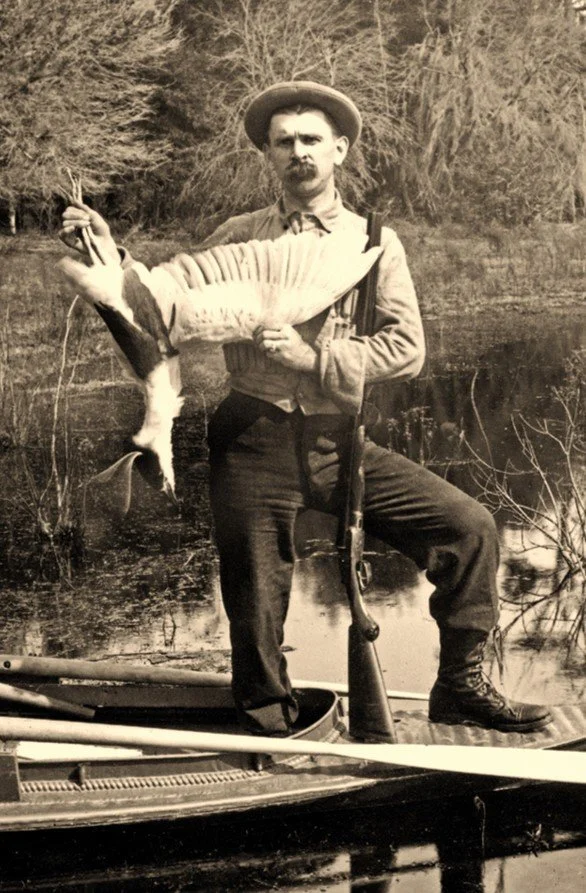

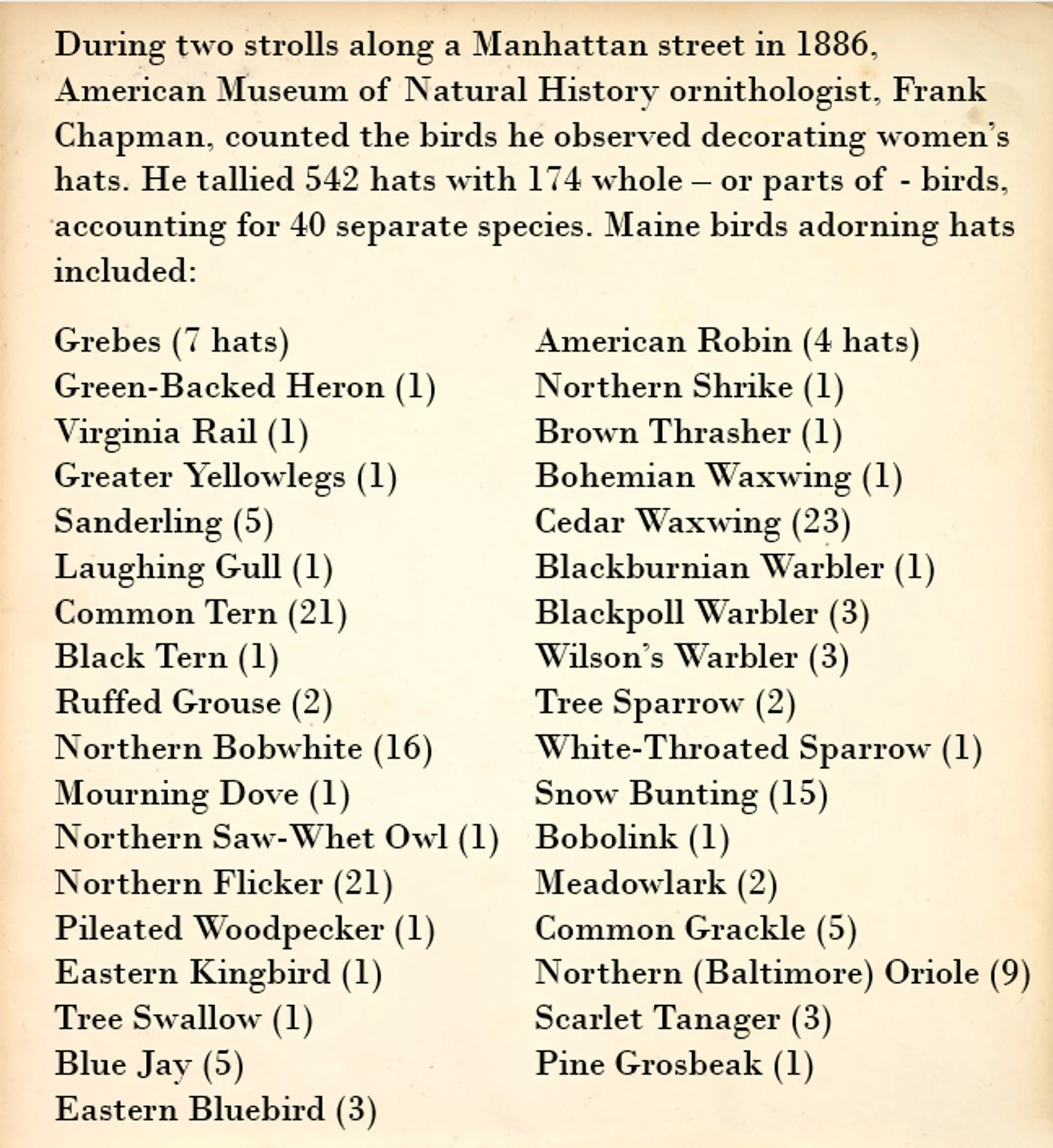

Decimation of Bird Populations. In 1886, up to 5 million birds were killed for their feathers to support the multimillion-dollar millinery and related industries; 50 North American bird species were being slaughtered and many faced extinction. No bird was too small; 41,000 hummingbird skins were purchased from a single London vendor during three sales in 1911. Harvesters often hunted in spring during nesting season when birds were in breeding plumage, leaving chicks unguarded and unfed, further endangering populations.

Some of Maine’s well-known birds, like our Great Egret, Snowy Egret, Great-Blue Heron, and Osprey, were targets of the millinery industry.

Two Women Made a Choice to Help Birds. In 1895 cousins Harriet Hemenway and Minna Hall, Bostonian socialites, helped sound the alarm for the irreparable harm “fashion” was inflicting on bird populations. During afternoon teas for their acquaintances they shared how hat choices were imperiling birds. Hundreds of women joined the effort to boycott feathered fashions and donned featherless “Audubonnets.”

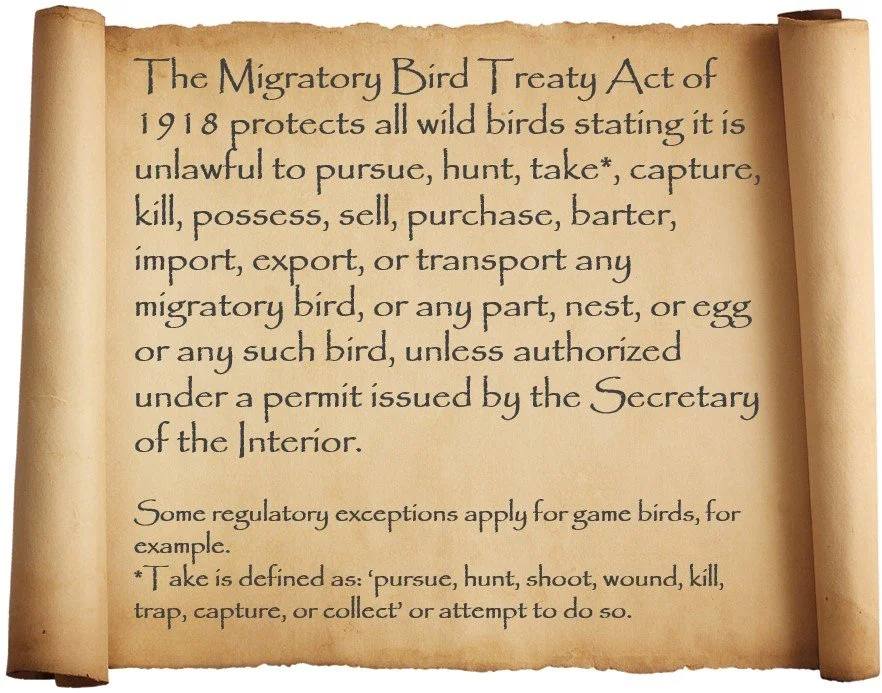

Effective Institutional change starts from the outside, influencing inward. That same year, the first Audubon Society – Massachusetts Audubon – was founded. Through the choices and efforts of these women, and others they inspired, state, and eventually federal, protections were enacted to protect birds, culminating in the federal Migratory Bird Act of 1918. While fashion and perspectives eventually shifted, illegal poaching occurs to this day, continuing to threaten birds and other wildlife. It is a global challenge, leading to the 1973 creation of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), brining together 181 countries to protect over 35,000 species for the future. Our daily personal choices - direct and indirect - can save species from vanishing.

Conservation efforts threatened the millinery industry, which attempted to portray bird harvests as sustainable, the women calling for change as silly, and the ensuing job losses as a peril to the economy. With time, much of the public understood the toll on birds and fashion tastes shifted, aided by the popularity of cars (big hats and car trips do not mix) and the onset of a World War.

However, as conservation work began to win the day, an underground-market trade emerged for those still desiring exotic, now illegal, feathers. Smugglers attempted to carry thousands of exotic birds, skins, and feathers over borders, concealed in suitcases, secured in clothing, and hidden in shipping containers. Wildlife conservation officers faced many challenges. One of the first game wardens in Southern Florida was killed by plume hunters in 1905. Soon after, another warden and an employee of the South Carolina Audubon Society died in the line of duty. These three deaths further galvanized individuals, organizations, and state and federal legislatures and essentially brought a close to the use of feathers in the fashion industry. Challenges remain today, with the illegal trade of feathers and birds continuing on the Internet and through age-old smuggling routes.

Ambassadors of Birdsacre. Birdsacre is subject to laws protecting birds and has federal and state permits to display some of Maine’s native birds. The non-releasable Avian Ambassadors allow us a rare, close-up view of our natural world so that we can better understand, appreciate, and protect it for birds and for ourselves.

Birds Face New Challenges Today. Our bird populations today, while protected from the feather trade, are declining at alarming rates. In Maine and beyond, they face habitat loss from development, environment degradation from pesticides and plastic pollution, and threats during migration, to name some challenges.

Further Exploration:

The Feather Thief: Beauty, Obsession, and the Natural History Heist of the Century: 2018, Kirk Wallace Johnson, Viking Press, New York, 320 pages. Additional resources: http://thefeatherthief.com/the-story/

Interview with Kirk Wallace Johnson, overview of events depicted, and additional resources: https://www.thisamericanlife.org/654/the-feather-heist

Felt, Feathers, and Fancy, Renton's Millinery Trade: 2018, Renton Historical Society & Museum Quarterly, Volume 49, Number 2. https://cdn5-hosted.civiclive.com/UserFiles/Servers/Server_7922657/Image/City%20Hall/Community%20Services/Museum/Newsletters/2018-06.pdf

Nearly 3 Billion Birds Lost to Us: Resources, including the original scientific paper, content summary, graphics https://www.birds.cornell.edu/home/bring-birds-back/

Seven Simple Actions to Help Birds: https://www.birds.cornell.edu/home/seven-simple-actions-to-help-birds/

Handout: https://www.birds.cornell.edu/home/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Seven-Simple-Actions-Oct-1.pdf

Tri-fold: https://www.birds.cornell.edu/home/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/7-Simple-Actions-trifold.pdf

A Hat Tip to the Women Who Started Modern Bird Conservation in the U.S., 2018, Pubita Saha, https://www.audubon.org/news/a-hat-tip-women-who-started-modern-bird-conservation-us

Meet the Undercover Crime Unit Battling Miami's Black Market of Birds, 2018, Rene Ebersole, https://www.audubon.org/magazine/fall-2018/meet-undercover-crime-unit-battling-miamis-black

References

Mrs. Charles B. Cowan of Seattle, Washington, wearing a hat with three taxidermied Carolina parakeets (now extinct), reflecting fashion of the 1900’s: Image from the Charles W. Sanders Collection, RHM# 2014.026.123, courtesy of the Renton History Museum, Renton, Washington.

Britannia fishing fly image: The Book of the Salmon; in Two Parts ... Usefully Illustrated with Numerous Coloured Engravings of Salmon-flies, and Salmon-fry, 1850, Edward Fitzgibbon and Andrew Young, Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, London, 294 pages, image from frontispiece. https://archive.org/details/bookofsalmonintw00fitz

Britannia fishing fly “recipe”: The Salmon Fly: How to Dress It and How to Use It, 1895, Kelson, Geo. M., Published by the Author c/o Messrs. Wyman & Sons, London, 510 pages, text p. 123. https://archive.org/details/salmonflyhowtod00kelsgoog/page/n2/mode/2up

Display case from circa 1865 containing North American birds: Auckland Museum, CC BY 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Case,_display_(AM_2006.14.1-1).jpg

1890 American bonnet with parakeets: Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bonnet_MET_37.144.2_d.jpg

A woman in a large feathered hat poses for a Gay Nineties fashion shot around 1895: Toledo-Lucas County Public Library, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gay_Nineties_Fashion,_Toledo,_Ohio_(approximately_1895)_-_DPLA_-_95d0cbd8e74bf74f0019455b79837cd9.jpg

Young egrets, unable to fly, left in nest after parents have been killed by plume hunters for their breeding plumage: Our Vanishing Wild Life, Its Extermination and Preservation, 1913, William T. Hornaday, Chapter XIII, Extermination of Birds for Women’s Hats, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/13249/13249-h/13249-h.htm

Plume hunter Leigh M. Pearsall posing with a Black-crowned night heron on Santa Fe Lake: Courtesy of the State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory, Image Number RC12766. https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/35148

1600 Hummingbird Skins at 2 Cents Each! Part of Lot Purchased by the Zoological Society at the Regular Quarterly London Millinery Feather Sale: August, 1912: Our Vanishing Wild Life, Its Extermination and Preservation, 1913, William T. Hornaday, Chapter XIII, Extermination of Birds for Women’s Hats, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/13249/13249-h/13249-h.htm#

List of birds observed by Frank Chapman (paraphrased): The Birder's Handbook: A Field Guide to the Natural History of North American Birds, 1988, Paul Ehrlich, David Dobkin, and Darryl Wheye, Touchstone (now Simon & Schuster), New York, 785 pages, p. 39.

Federal agents with confiscated egret skins, 1930s: Photograph by H.B. Thrasher, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, National Conservation Training Center Archives/Museum.

Featherless, birdless, humane Audubonnet: https://www.audubon.org/news/a-hat-tip-women-who-started-modern-bird-conservation-us

A Great Egret family at a natural rookery at St Augustine Alligator Farm Zoological Park, USA, parents with a chick on a nest are in the foreground: AdA Durden from Jacksonville, CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/, via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ardea_alba_-St_Augustine_Alligator_Farm_Zoological_Park,_USA_-nest-8.jpg

Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 (paraphrased): https://www.fws.gov/law/migratory-bird-treaty-act-1918, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2017-title16/pdf/USCODE-2017-title16-chap7-subchapII.pdf

An Osprey flying in Sandy Hook, New Jersey, USA: Peter Massas, CC BY-SA 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/, via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pandion_haliaetus_-Sandy_Hook,_New_Jersey,_USA_-flying-8.jpg

A pair of Great Blue Herons hug on their new nest: Andy Morffew from Itchen Abbas, Hampshire, UK, CC BY 2.0, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/, via Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Hug_(8431739874).jpg

7 Simple Acts to Help Birds: Cornell Lab of Ornithology. https://cornell.app.box.com/v/3BillionBirds/file/634482724945